555-555-5555

mymail@mailservice.com

Eucharist: An Opportunity for Familial Reception?

The following article, produced here by permission, was published in One in Christ, 52/1, 2018, pp. 31-39a publication of the Olivetan Benedictines of Turvey and Rostrevor, UK, pp 31-39.

Eucharist: An Opportunity for Familial Reception?

Ray Temmerman*

In the Code of Canon Law of the Roman Catholic Church, Canon 844 §1specifies the administration of the sacraments to Catholics alone. It then immediately goes on to allow for exceptions.[1] Can. 844 §2allows Catholics, when there is no availability of Eucharist within their own Church, to receive from non-Catholic ministers in whose Churches the sacraments are valid.[2]

Two corollaries to this part of the canon should be noted. First, in order to receive the Eucharist in this situation, it must be appropriate, from the Catholic perspective, to be received by those ministers and their Churches. Second, given that some of those Churches are not welcoming of people who are not their members, it must be equally appropriate for Catholics to, in the words of Susan K. Wood, ‘risk the real pain, the profound embarrassment, the wrenching experience of exclusion’[3] that may result from engagement with such ministers and their Churches.

Canon 844 §3 allows for Catholic ministers to administer the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and anointing of the sick licitly to members of Eastern Churches which do not have full communion with the Catholic Church if they seek such on their own accord and are properly disposed. One might presume that this applies only when ministers of their own Eastern Churches are not available, however it doesn’t actually say that. It appears sufficient that such Christians be properly disposed, and seek participation (i.e. this is something they actively do of their own volition) in the sacraments within the Catholic Church.

Finally, there is the question of reception of people of other Christian traditions within the Catholic Church. Can. 844 §4. states ‘If the danger of death is present or if, in the judgment of the diocesan bishop or conference of bishops, some other grave necessity urges it, Catholic ministers administer these same sacraments licitly also to other Christians not having full communion with the Catholic Church, who cannot approach a minister of their own community and who seek such on their own accord, provided that they manifest Catholic faith in respect to these sacraments and are properly disposed.’

The conditions are clearly outlined, and are expanded on in the Directory on Ecumenism.

The DAPNE and Exceptions

The Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism (DAPNE) states that where the Eucharist, penance, and the anointing of the sick are concerned, ‘in certain circumstances, by way of exception, and under certain conditions, access to these sacraments may be permitted, or even commended, for Christians of other Churches and ecclesial Communities.’[4]

Exceptions, as you know, are not situations in which the law can be broken, but rather situations in which the law does not apply, something outside of, or beyond, the norm. The norm involved here is that the sacraments are for those in full communion with the worshipping community. The exception, if granted, would be to extend sacramental participation to a person not in full communion with the worshipping community.

Some dioceses and episcopal conferences have published their own directories on Eucharistic sharing, with some giving lists of events to serve as examples of where an exception may be granted. Where such exceptions have been granted, they have been welcomed and celebrated. What has been the experience of the faithful regarding the granting of exceptions?

While not able to speak for all, I can provide some indication from the perspective of interchurch families, couples bound together as brothers and sisters of Christ through baptism, and made one in marriage. Living in their marriages ‘the hopes and difficulties of the path to Christian unity’,[5] they ‘can lead to the formation of a practical laboratory of unity’.[6] As such, they are on the frontlines of this issue, impacted Sunday by Sunday, most often (though not exclusively) within the Catholic Church. They find themselves, as per Derrida, lodged within the traditional conceptuality, where are found the fissures and wounds of the tradition, ‘challenging the very order of it in order to move to a new time, an unexpected thing and different place.’[7] Their experience indicates several responses.

- In practice, such lists have often been taken as exclusionary, i.e. if the event is not listed, no exception is deemed possible.

- It is presumed that a minister of the person’s tradition is always available, even in cases where the couple, that one made so by marriage, is worshipping together. It would appear the spouses must make a choice: either 1) they uphold the unity of their marriage, and refrain as one from receiving the sacrament in recognition of the divisions between their churches, or 2) they deny the unity of their marriage in order to receive individually the sacrament of unity in their respective traditions—and in that denial perhaps render themselves improperly disposed.

- There is a presumption that the person of another tradition does not have a Catholic faith in the Eucharist.

- The issue of disposition is seldom broached.

I offer these observations, not by way of criticism, but to indicate that there is a real need to delve more deeply into our understandings of exceptions. I invite you to explore with me a context, theological, ecclesiological and anthropological, whose exceptionality calls for the exceptions possible in canon law.

In Baptism, we are made by adoption what Christ is by origin, raised from our natural human condition to the dignity of sons and daughters of God.[8] We become members of Christ, and are ‘incorporated in the Church’.[9] We are formed into God’s people. This is the case for all who are baptized, provided the minister of baptism has ‘the intention of doing what the Church does’,[10] and that the baptism is conducted with water and the trinitarian formula.[11] This is tremendously and wondrously inclusive.

Against this sense of inclusion, there is a history of speaking, at least in English, of brothers and sisters in Christ, who enjoy membership in Christ’s Body, the Church, albeit through other Christian traditions, as being ‘separated brethren’. This term has led many to see those brothers and sisters as somehow ‘other’, not really ‘one of us’. Therefore, it’s worth looking at its origins.

Orientalium Dignitas (1894),[12] while addressed to the Eastern Churches, spoke of fratres dissidentes, or dissident brothers. They are our brothers, but we don’t get along. Orientalium Ecclesiarum (1964),[13] also speaking of relations with the Eastern Churches, spoke of fratres seiunctos, a term translated into English as separated brethren. That same term is taken up in Unitatis Redintegratio (1964), where once again it is translated into English as separated brethren.

It’s important, however, to look at the understanding of the Latin term. According to G.H. Tavard, one of the drafters of Unitatis Redintegratio, Cardinal Baggio, a noted Latin scholar, requested that the term seijuncti be used instead of separati. Separati, he argued, ‘would imply that there are and can be no relationships between the two sides; seijuncti, on the contrary, would assert that something has been cut between them, yet that separation is not complete and need not be definitive.’[14] Tavard suggests a more appropriate terminology would be to speak of estranged brothers rather than separated. The nuance does not come through well, if at all, in the English translation, yet the difference in nuance is important.

Rather than seeing Christians of other traditions as being somehow separated from the body, needing to be reattached to have life, we can rightly see them as still connected, still part of the same body of which we, as individuals, also form part. Even though the bodily tissue is damaged and in need of healing, the body is still one. There is still in some way a flow of nutrients, of neurological signals, between the parts. Unity still exists, is still real, though in a manner which is less than perfect.

That lack of perfection, however, lies not at the level of being truly brothers and sisters, but at the level of estrangement between true brothers and sisters.

What would happen if we began referring to Christians of other traditions as brothers and sisters from whom we are estranged? Would we perhaps begin more clearly and easily to recognize them as still part of the same body of which we are also part, still connected, even though the body may be damaged, the connections tenuous and in need of repair? Would we see that estrangement requires two to be involved, i.e. that we have as important a role to play in lessening the estrangement between us as does the person from whom we are estranged?

Dinner in the household of God.

To slightly modify a phrase by Susan K. Wood, even though all people are born into the human community, and thereby experience union with one another within this common reality, our incorporation into that community takes place only within a particular concrete household.[15] It is normal and normative that we humans eat and drink in our own household, where we are familiar with the family’s recipes and rituals. While, in more affluent societies, it is now more common to ‘go out’ to eat, trying different restaurants, with their varied ambiances, recipes and flavours, the norm is still to eat in one’s own home. To eat in another’s home, even that of a brother or sister, is exceptional. And to do so in the home of a sibling from whom one is estranged, is exceptional indeed. This, I suggest, is an appropriate context for the Directory’s use of the term ‘exception’.

To go into the home of a family member from whom one is estranged, there to eat and drink with that member, where access to one’s own recipes and rituals is unavailable, is an activity full of risk, and therefore rightly an exception. One does not know if one will be received in welcome (even if the receivers are equally fearful), or rejected, turned away. Nor is one familiar with the rituals, the behaviours considered appropriate. One believes only, with that sibling, that there is real food here, and real drink, and that eating and drinking together can help to heal the estrangement, restore the family unity.

It may be that such eating and drinking takes place around a baptism, a wedding, a funeral, events which hold a certain commonality, and hence reduce the risk. But I would argue that the events themselves are not the exception. Rather, they reveal the primary exception which, I would also argue, is the act of going outside one’s own home, to the home of a family member from whom one is estranged, with all the risk that entails, there to eat and drink together with the intent[16] of building family unity, reducing the estrangement.

For an estranged sibling to receive in a ‘non-home’ Church or ecclesial community involves two acts of reception. The one we are most familiar with, the one spoken of in canon law, is that of the estranged sibling receiving the Eucharist. But there is a second, namely that of the Church or ecclesial community receiving that sibling.

The presence of an estranged sibling in the community’s central act of worship constitutes a call to that community to receive that estranged sibling. How will the community respond? With a presumption that the sibling rejects the community’s self-understanding, its guidelines for table etiquette? Or with a presumption that, even if the specifics of that etiquette are unknown by the sibling (as can often be the case), the sibling is seeking to reduce the estrangement, restore the body? Will the body of Christ be recognized as present only in the sacred elements, or also in the person of the estranged sibling (1Cor.11:29)? The selected presumption, conscious or subconscious, will largely dictate the community’s response, for rejection or reception.

If we take the words of the canon, and obey them, I suggest we will find it very difficult to receive anyone from outside our Church or ecclesial community without extreme vetting, based on a presumption that such people fall short of our required table etiquette. If, on the other hand, we take those same words and apply them within the context of an exceptional act, I suggest we will find ourselves far more able to receive the gift of God present in the form of the estranged sibling.

Returning to canon 844 §4, I also ask: is the very desire to reduce estrangement between brothers and sisters, a response (even if unwitting, i.e. it never specifically enters a person’s mind that this is what is being done) to Christ’s call that all be one, not itself of sufficient gravity to warrant administration of the Eucharist to Christians not fully in communion with us, provided all the remaining criteria are met?[17]

Let us not forget that ‘the res et sacramentum of Baptism … is membership in the Church,’[18] and that ‘the res et sacramentum of the Eucharist is not just the risen body of the Lord, but the whole Christ, the Church.’[19] This must surely include those brothers and sisters who have come to our home, the home of siblings from whom they are estranged, there to eat and drink with those siblings.

I return, then, to the original question encapsulated in the title of this paper: can we find it in ourselves to receive an estranged member of the family who risks joining us for a meal, with our presuming, not that this family member is an abuser of family ties, merely out to see how the relatives live, but one like us, a pilgrim on the way to the unity for which Christ prayed? In such a situation, can the Eucharist, rather than a sign of delineation and separation, be viaticum, food for the journey for all who receive?

If so, then the Eucharist can indeed become an opportunity for familial reception.

*Ray Temmerman (Catholic) is married to Fenella (Anglican). Both are active in the Interchurch Families International Network and together in their two churches (http://interchurchfamilies.org). Their experience of actively participating and worshipping together in both churches has led Ray to begin research on the topic ‘Interchurch Families and Eucharistic Sharing: In Search of a New Hermeneutic’.

[1] Code of Canon Law, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1983), hereinafter referred to as ‘Code’. Canon. 844§1. Catholic ministers administer the sacraments licitly to Catholic members of the Christian faithful alone, who likewise receive them licitly from Catholic ministers alone, without prejudice to the prescripts of §§2, 3, and 4 of this canon, and can. 861, §2.

[2] Code, Canon 844§2. Whenever necessity requires it or true spiritual advantage suggests it, and provided that danger of erroror of indifferentism is avoided, the Christian faithful for whom it is physically or morally impossible to approach a Catholic minister are permitted to receive the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and anointing of the sick from non-Catholic ministers in whose Churches these sacraments are valid.

[3] Cf Susan K. Wood, ‘We've lost the ecclesial meaning of the Eucharist.’ Compass: A Jesuit Journal, Mar.-Apr. 1997, p. 30. Canadian Periodicals Index Quarterly, hereinafter referred to as ‘Wood’.

go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=CPI&sw=w&u=winn62981&v=2.1&id=GALE%7CA30523199&it=r. Accessed 5 July 2017.

[4] Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1993), Article 129, accessed 15 Oct. 2017:

http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/documents/rc_pc_chrstuni_doc_25031993_principles-and-norms-on-ecumenism_en.html

[5] Homily of John Paul II, York, England, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1982), #3, accessed 15 Oct. 2017:

[6] Address of Benedict XVI, Warsaw, Poland, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2006).

https://w2.vatican.va/content/benedictxvi/en/speeches/2006/may/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20060525_incontro-ecumenico.html accessed 2 Mar 2018.

[7] Claudio Carvalhaes, ‘Borders, Globalization and Eucharistic Hospitality’, Dialog 49 no 1 (2010), p 45-55, p. 48.

[8] Cf Avery Dulles, Models of the Church, (New York: Doubleday, 2002), p. 46.

[9] Lumen Gentium, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1964), # 11.

[10] Decree for the Armenians, (Council of Florence, 1439); and also Decree on the Sacraments, (Council of Trent, 1547), Canon 11, cited in Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism,(Oak Grove MN: Winston Press, 1980), hereinafter referred to as ‘Catholicism’.

[11] Catechism of the Catholic Church, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1993), #1271. Baptism constitutes the foundation of communion among all Christians, including those who are not yet in full communion with the Catholic Church: ‘For men who believe in Christ and have been properly baptized are put in some, though imperfect, communion with the Catholic Church. Justified by faith in Baptism, [they] are incorporated into Christ; they therefore have a right to be called Christians, and with good reason are accepted as brothers by the children of the Catholic Church. Baptism therefore constitutes the sacramental bond of unity existing among all who through it are reborn.’

[12] Orientalium Dignitas, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1894), http://www.papalencyclicals.net/leo13/l13orient.htm,accessed 17 June 2017.

[13] Orientalium Ecclesiarum, (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1964), http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19641121_orientalium-ecclesiarum_en.htmlaccessed 17 June 2017.

[14] G.H. Tavard, ‘Reassessing the Reformation,’ One in Christ, 19 (1983), pp. 360-361.

[15] Wood, p. 30. Her original phrase is ‘Even though all Christians baptized with the water bath in the name of the Trinity are incorporated into the death and resurrection of Jesus, and thereby experience union with one another within this common baptism, our incorporation into Christ and the Church takes place only within a particular concrete ecclesial community.’

[16] An example, by way of clarification of what I mean by intent might be in order. When my wife and I invite a sibling and his/her spouse to our home for a meal, we do so in the simple joy of getting together. We serve as hosts, they as guests; we have a good time together, after which they return to their home. Our guests are, indeed, my sibling and his/her spouse, but they could be anyone. There is, moreover, no intent to strengthen family bonds, though that may well be an unintended outcome. On the other hand, when I and my siblings, each of us with our spouses, gather every third month for a sibling dinner, we do so with the specific intent of nurturing and enhancing family bonds. We meet in the home of one or other of the siblings, and share a meal together, a meal prepared from the offerings of each. At the end of our time, we each return to our own homes, to continue our journey of life. But in the process, we have strengthened our family bonds, built the capacity to work through differences, made our family more ‘one’.

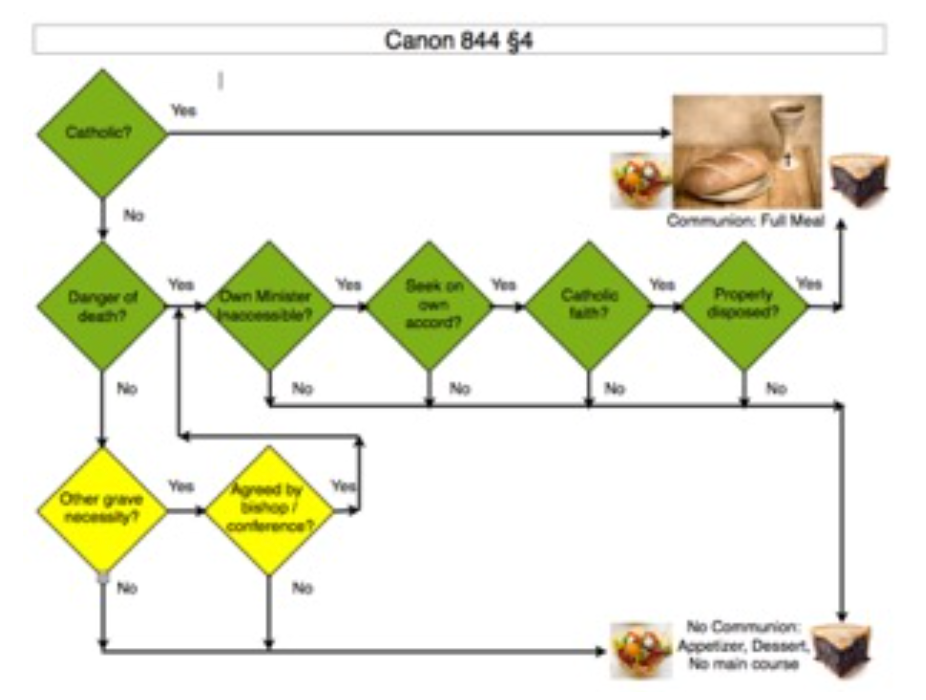

[17] Note that the wording of the canon presents challenges. One might think that the criteria of §4 (cannot approach a minister of their own community, etc.) serve as the deciding factor in determining whether or not an exception can be granted to share the Eucharist. While the criteria may offer guidance in determining levels of ecclesiality, the fact is that people of other traditions seldom get far enough to have their case tested against the criteria. In the vast majority of cases, the question of exception is determined on the basis of serious necessity, itself determined according to criteria of imprecise determination, and almost invariably unknown by the person(s) impacted by the determination. There would seem to be no way of knowing what level the bar is which one must leap over before reaching and being tested against the specified criteria. The appended flow chart shows that more clearly.

Contact Us

3rd Floor,

20 King Street,

London,

EC2V 8EG.

Contact Us

Telephone: +44 (0)20 3384 2947

Email: info@interchurchfamilies.org.uk

Registered Charity No. 283811